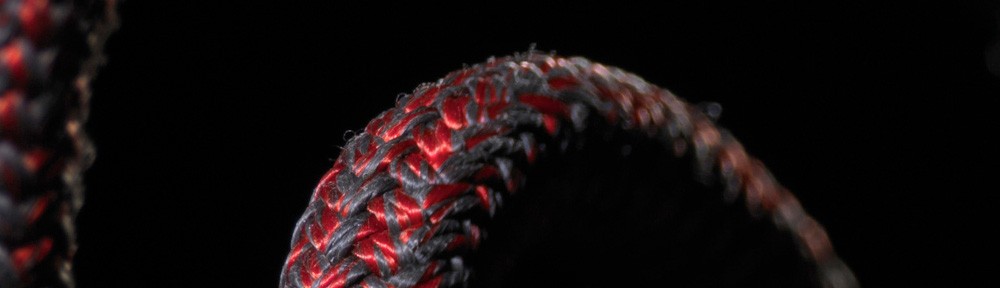

Cover ConstructionsAll Grand Prix Series ropes are fully customisable. Different cover constructions have different properties and performance characteristics.24 plait – thicker cover, offers excellent grip, good durability and flexibility. Easy to splice with all core configurations and is the standard cover construction for most running rigging applications32 plait – thinner cover, smooth running through blocks and sheaves. Often used when a larger core is needed for strength without increasing diameter, but is more technical and time consuming to splicethan 24 plait.48 plait – very thin cover, very smooth and easily expandable. Normally made with Dyneema® offering outstanding resistance to abrasion so used for chafe gear and covers for loops and lashings. Also used for standing rigging overbraids.

Grand Prix rope solutions for a winning performance

MGP Core TechnologyMarlow’s Grand Prix Series offers a range of core options using Dyneema®, Vectran® and Zylon® (PBO). Each material has its own particular strengths and weaknesses.Dyneema® offers by far the best strength to weight ratio of any material used in rope manufacture and is the material of choice for high performance cores. At Marlow we offer a range of Dyneema® cores to suit strength and handling preferences as well as budget.Dyneema®is an Ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene (UHMWPE) and is available in a number of different grades. All grades of Dyneema® have excellent fatigue resistance (cyclic bending), UV resistance and abrasion resistance, but have poor heat resistance due to a relatively low melting point.SK78 is the standard material offering very high strength but significantly improved creep characteristics over its predecessor SK75 or equivalents.SK99 It offers exceptional strength (some 20% higher than SK78) and is unmatched in terms of strength to weight ratio.DM20 has slightly lower tenacity than SK78, but has one major advantage in that it exhibits virtually zero creep, which can often have a negative effect on a rope’s performance and strength, at high loads for an extended period.Vectran® (LCP) has the best creep performance of any synthetic fibre and can offer improved resistance to heat compared to the UHMPE family, but is far heavier.Zylon® (PBO) offers unrivalled strength/diameter performance coupled with exceptional resistance to heat and ultra-low elongation. However, PBO is very susceptible to UV degradation.

Everything you need to know about lifejackets

Research shows that lifejackets drastically improve survival rates by up to four times when immersed in cold water. They also help keep you safe and afloat in situations where you may need rescuing. As we head into the new season, here are some frequently asked questions surrounding lifejackets and how to stay safe on the water. Are lifejackets compulsory on boats? No, but the RYA’s advice is to wear a lifejacket or buoyancy aid, unless you’re sure it’s safe not to. Your decision should be based on weather conditions, the type of on-water activity and your level of experience. Lifejackets are suitable when on an open boat (powerboat or RIB), when going ashore in a yacht tender and on a sailing yacht or motor cruiser. Lifejackets or buoyancy aids – what’s the difference? With buoyancy aids, you are required to swim or continuously move to help keep your face above water. Alternatively, a lifejacket provides face-up in water support. If you fall overboard unconscious, a lifejacket provides safety on the water by turning you over so you can breathe. Lifejackets are also fitted with a whistle, lifting loop and retroreflective material. For those more suited to offshore, crotch straps, harness, a light and sprayhood will be included. Buoyancy aids are suitable for personal watercraft (PWC), dinghies, windsurfing and generally for activities where the wearer might reasonably expect to end up in the water. What do the levels of buoyancy mean? Buoyancy aids and lifejackets have different levels of buoyancy to ensure safety on the water. There are four main buoyancy levels: 50, 100, 150 and 275. In general terms, Level 50 is a buoyancy aid designed for when help is close at hand. Level 150 is a general-purpose lifejacket more suited to offshore cruising and motor boating. The RYA strongly recommends not wearing a 275 lifejacket, as this is very bulky when inflated and will obstruct you if getting into a life raft. Learn about the different levels of buoyancy for staying safe on the water. Do I need to professionally service my lifejacket? For recreational boaters, there’s no legal requirement to get your lifejacket serviced. However, lifejacket manufacturers do recommend their products be annually serviced by a professional at an approved service station. Annual servicing is a requirement for SOLAS approved lifejackets for professional use. What checks can I do myself? Throughout the season check your lifejacket for signs of damage to the bladder cover, webbing straps, stitching, clips, and buckles. You should also ensure that any ‘life’ parts are in date and regularly check the inflation cylinder has not been discharged and that it’s fitted properly. If you are concerned, get it looked at. Discover how to look after your lifejacket and stay safe on the water. How do I clean my lifejacket? After use, rinse off any salt, sand, or stains with clear water. Salt can be corrosive and damaging plus nobody wants to use a musty lifejacket! Once clean, dry out of direct sunlight. Lifejackets should be stowed completely dry, somewhere cool, and dark. Lifejackets for children- what do I need to consider? Lifejackets are recommended for children, toddlers, and babies to support the head and keep the wearer facing upwards in the water. Anyone wearing a buoyancy aid should be a confident swimmer. Guidelines suggest getting a lifejacket that fits your child now rather than to grow into. A good way to judge this is to fit and adjust the life jacket on the child and then lift the life jacket from the top. You shouldn’t be able to lift it more than 2.5cm from the child’s shoulders if the fit is correct. What about pets? A buoyancy aid will also keep your pets safe on the water and aboard. We recommend giving your fury friend a chance to get used to wearing its life jacket before actually getting on a boat – and it’s a good idea to allow your pet to practice swimming while wearing its jacket too.

Med-mooring: Stern-to

Mediterranean mooring, also known as ‘Med mooring,’ is a technique for securing a vessel to a pier or dock. It takes its name from the traditional Mediterranean custom of mooring stern-to along a town quay or marina. This method works well in the Med as there is very little tide, and it is a more efficient use of dock space. If you’re planning a charter holiday or to take your boat to the Med this summer, you’re likely to encounter Med mooring in destinations like Greece, Croatia and Italy. Med mooring Mediterranean mooring is usually stern-to the quay, allowing for easy access ashore. However, if unsure of the water’s depth, going bows-to will keep your drives in deeper water. Stern lines are used to stay close to the quay or pontoon, and either an anchor or a line from the bow helps hold the boat away. A passerelle or wooden plank is usually carried by the boat and set down when leaving your vessel to go ashore. When mooring abroad, you should talk to the marina or town quay to agree a berth or chose a preferred spot. Between other vessels is preferable. You’ll also need to confirm how to secure the bow, either with lazy lines or an anchor. Here are a few basics to help you with Med mooring stern-to… Stern-to with lazy lines Lazy lines Lazy lines are used in busy harbours and marinas where multiple anchors would become fouled. Instead of the anchor holding the bow away, the bow is connected to a heavy bow line, which is pre-attached to a concrete block on the seabed. The bow line is also attached to a lighter ‘lazy line’ leading to the quayside/pontoon. The lazy line is retrieved from the wall and led to the bow and the heavier line hauled in and tied off. Preparation Rig up the fenders on either side and at the stern. Follow by rigging two stern lines, they should be long enough to go ashore and come back to the boat. The approach Reverse towards the quay/pontoon and connect windward stern line to quay/pontoon first. Pick up the lazy line, lead it to the bow and tie off. Connect the second stern line and then adjust bow and stern lines. To hold the boat in position once the windward stern-line is attached use small nudges ahead on the leeward engine. If you have a single engine boat, turn the wheel to windward and use ‘ahead’ to keep the bow up to wind. Often the stern lines are eased, and the bow line is re-tightened. The stern lines are then hauled in taught. A tight bow line reduces the chance of the stern bashing the quay or pontoon. Springs which are diagonal lines from either quarter to the quay can stop the stern from moving sideways. Stern-to under anchor In harbours with no lazy lines, you’ll need to drop your anchor. Preparation Rig up fenders on both sides and a large fender on the stern. Once complete, rig a stern line from both quarters. Prepare the anchor to drop, ensuring that the chain is either flaked out on the deck or untangled in the chain locker, so it runs freely. If possible, look at where other vessels anchor chains are laid and don’t cross them with yours. The approach Reverse towards your intended berth, start from a good distance away to ensure the vessel is under control. When you get to roughly four boat lengths away from the quay, drop the anchor and ease out chain, this needs to runout easily. When you get to one boat length away from the quay, stop easing the chain so that any kinks are removed, and the anchor digs in. Be ready to ease out more chain if required. Connect the windward stern line to shore, followed by the leeward stern line. Once positioned the correct distance from the quay, take the strain up on the chain. To ensure the stern stays away from the quay/pontoon, often the stern lines are eased, and the chain tightened. Crosswinds In a crosswind it may be necessary to reverse into wind initially to get steerageway. It is imperative that the chain runs out freely or there is potential it will snub the bow and alter or ruin your approach towards the berth. When slightly upwind of the gap, drop the anchor and reverse into the space. Ensure the leeward side is protected with fenders in case you drift onto the downwind boat. Onshore wind If the wind is on the bow, treat stern-to Med mooring as a normal anchoring exercise. Drop the anchor four-boat lengths out and gently reverse into the gap with the stern lines ready. Once you are roughly one boat length away from the quay, snub the anchor so that it digs in. You can then finish by connecting the stern lines. Enhance your skills Gain a better understanding of Med mooring and boat handling through our training courses or take a look at our RYA Boat

Source: Med-mooring: Stern-to

“We want Great Britain to win top nation again” “We’ve been sprinting ever since Tokyo, because of the compressed Olympic cycle since Tokyo 2020,” says RYA Performance Director, Mark Robinson. “Of course, it’s the same for every nation, but there hasn’t been the usual year for resting and resetting, which is typically what people do in the year after a Games. We just had to get straight back into it. “It’s especially fast-paced because four of the ten events are new to the Olympic circuit. Not only that, but men’s and women’s events in foiling kiteboarding and foiling windsurfing both run brutal Medal Series formats which place enormous emphasis on performing on the final day. Sailors used to be able to put together a consistent series across the whole regatta. Now sailing joins sports such as running and swimming in deciding the medals in a sudden death final.” Robinson acknowledges that sailing has some significant differences that might well warrant the traditional model of rewarding a consistent performance across the week. “In sailing we’re working with a dynamic field of play where all kinds of factors – variable wind, waves, weather – can all heavily influence the outcome. But we’re in the Olympics and this is the way televised sport is going, so we’ve had to make sure our athletes are mentally prepared for these final-day formats.” While much about the equipment and setup has changed since Tokyo, the medal target agreed with UK Sport remains three to five medals of any colour. “I think it’s very achievable,” says Robinson. “We’ve got good medal prospects across quite a few of the classes but, of course, we want Great Britain to win top nation again. And for that we’ll probably need some golds, and that’s the goal we set for ourselves at every Games.” The team within the team It’s sometimes said that, where athletes in other sports achieve personal bests and world-record times at the Olympic Games, in sailing competitors often perform below their best. Luckily the British Sailing Team has tended to buck this trend, nearly always rising to the big occasion. Of course, it’s not really luck at all, but part of the design of the team’s structure. A big part of Team GB’s success is the support staff working behind the scenes, helping to bring out the best of our sailors. It’s also the camaraderie between the whole team. Once a sailor has finished their Olympic regatta, they stay to support to everyone else, all the way to the closing ceremony. Kate Eddy, Head of Performance Support, is a member of this highly experienced team. She’s a strength and conditioning coach and biomechanist approaching her eighth Olympic and Paralympic Games, and has worked at the top level in a range of men’s and women’s sports. “I’m a surfer in my spare time, so I’ve got an interest in the sea and find sailing absolutely fascinating,” says Eddy. “Compared with most sports, where the athletes are operating in a more controlled, predictable environment, sailors have to cope with such a random and ever-changing field of play. It’s incredible how they manage such a complex scenario.” Eddy says the focus is on ensuring the sailors are prepared physically and mentally. “The challenge of the new board sports is the high speeds and potential for crashing, so we’ve worked closely on injury prevention,” says Eddy. “But the other side is the sudden-death nature of their finals, and to make sure they are in the right mindset to perform in that critical moment.” Find out more The Olympic sailing events will take place from 28 July to 8 August and will be aired on Discovery+. For more information about the Games, our team of 14 British sailors and windsurfers, the Olympic sailing classes and all the latest news, visit our Paris 2024 hub.

“We want Great Britain to win top nation again” “We’ve been sprinting ever since Tokyo, because of the compressed Olympic cycle since Tokyo 2020,” says RYA Performance Director, Mark Robinson. “Of course, it’s the same for every nation, but there hasn’t been the usual year for resting and resetting, which is typically what people do in the year after a Games. We just had to get straight back into it. “It’s especially fast-paced because four of the ten events are new to the Olympic circuit. Not only that, but men’s and women’s events in foiling kiteboarding and foiling windsurfing both run brutal Medal Series formats which place enormous emphasis on performing on the final day. Sailors used to be able to put together a consistent series across the whole regatta. Now sailing joins sports such as running and swimming in deciding the medals in a sudden death final.” Robinson acknowledges that sailing has some significant differences that might well warrant the traditional model of rewarding a consistent performance across the week. “In sailing we’re working with a dynamic field of play where all kinds of factors – variable wind, waves, weather – can all heavily influence the outcome. But we’re in the Olympics and this is the way televised sport is going, so we’ve had to make sure our athletes are mentally prepared for these final-day formats.” While much about the equipment and setup has changed since Tokyo, the medal target agreed with UK Sport remains three to five medals of any colour. “I think it’s very achievable,” says Robinson. “We’ve got good medal prospects across quite a few of the classes but, of course, we want Great Britain to win top nation again. And for that we’ll probably need some golds, and that’s the goal we set for ourselves at every Games.” The team within the team It’s sometimes said that, where athletes in other sports achieve personal bests and world-record times at the Olympic Games, in sailing competitors often perform below their best. Luckily the British Sailing Team has tended to buck this trend, nearly always rising to the big occasion. Of course, it’s not really luck at all, but part of the design of the team’s structure. A big part of Team GB’s success is the support staff working behind the scenes, helping to bring out the best of our sailors. It’s also the camaraderie between the whole team. Once a sailor has finished their Olympic regatta, they stay to support to everyone else, all the way to the closing ceremony. Kate Eddy, Head of Performance Support, is a member of this highly experienced team. She’s a strength and conditioning coach and biomechanist approaching her eighth Olympic and Paralympic Games, and has worked at the top level in a range of men’s and women’s sports. “I’m a surfer in my spare time, so I’ve got an interest in the sea and find sailing absolutely fascinating,” says Eddy. “Compared with most sports, where the athletes are operating in a more controlled, predictable environment, sailors have to cope with such a random and ever-changing field of play. It’s incredible how they manage such a complex scenario.” Eddy says the focus is on ensuring the sailors are prepared physically and mentally. “The challenge of the new board sports is the high speeds and potential for crashing, so we’ve worked closely on injury prevention,” says Eddy. “But the other side is the sudden-death nature of their finals, and to make sure they are in the right mindset to perform in that critical moment.” Find out more The Olympic sailing events will take place from 28 July to 8 August and will be aired on Discovery+. For more information about the Games, our team of 14 British sailors and windsurfers, the Olympic sailing classes and all the latest news, visit our Paris 2024 hub.

Can our sailors do it again? Ever since that breakthrough performance at the Sydney 2000 Games when Great Britain’s sailors took home three golds and two silvers from Australia, the British Sailing Team has set the benchmark for the rest of the world to follow. Achieving top nation – the country with the most medals – at the Games is never a straightforward task. With the Covid pandemic delaying the Tokyo 2020 Games by a year, there have only been three short years for the sailors and support staff to get ready for Paris 2024. And that mainstay of golden success, the Finn heavyweight dinghy, is no longer part of the Games. The Finn had been a phenomenal gold medal factory for Team GB, with Iain Percy, Ben Ainslie and Giles Scott collectively taking the top step of every podium, going all the way back to Sydney. However, in the past few years the British Sailing Team has been working hard to get to the top of the new Olympic events – kiteboarding, known as Formula Kite, and the foiling windsurfer, known as iQFOiL. Along with the foiling catamaran, the Nacra 17, this means that five of the ten Olympic events are now high-speed hydrofoilers. There has been a changing of the guard too. Some of Great Britain’s multi-medallists like Giles Scott, Hannah Mills and Stu Bithell have moved on to other challenges in professional sailing like SailGP and the America’s Cup. However, this year’s team will include Tokyo silver medallists in the Nacra 17, John Gimson and Anna Burnet, and Tokyo bronze medallist Emma Wilson who’s now flying high on the new iQFOiL board. While the bulk of the Olympic sports will be taking place in France’s capital city, the sailing regatta is being hosted by the city of Marseille on the Mediterranean coast. The city is surrounded by the vast mountain ranges of Sainte-Baume and Etoile. The complex geography, mixed with a hot Mediterranean climate and the potential for dry winds from the Sahara, makes Marseille an unpredictable venue for sailing. There are plenty of countries hoping to knock Great Britain off its perch as sailing’s acknowledged high-flier. While Australia and New Zealand are not looking quite so strong this time round, a number of European nations could be serious rivals to Team GB. Not least of these is the host country France, along with strong challenges from Spain, Germany, Italy and The Netherlands.

Oyster Yachts open up the world for a new generation of owers | City & Business | Finance | Express.co.uk

Oyster Yachts open up the world for a new generation of owners British luxury boat maker Oyster Yachts has the wind in its sails as a new breed of adventurer discovers the seductive sleek beauty of its vessels, their exhilarating agility and the support of the company’s global service network ensuring comfort and safety. By MAISHA FROST 13:20, Fri, Jun 14, 2024 | UPDATED: 13:20, Fri, Jun 14, 2024 1BOOKMARK Buoyant and beautiful: Oyster’s latest 50ft 495 yacht (Image: Oyster Yachts) British luxury boat maker Oyster Yachts has the wind in its sails as a new breed of adventurer discovers the seductive sleek beauty of its vessels, their exhilarating agility and the support of the company’s global service network ensuring comfort and safety. Known for its supreme craftmanship combining traditional skills and advanced technology, Oyster’s hand-built cruisers are the blue water sailing, long haul kind, able to go anywhere and withstand the elements’ sternest tests. Awareness of climate change and sustainability have also increased interest in the brand’s wind-power credentials. “The future of our oceans is in all our hands, by its very nature Oyster is sustainable and we are committed to becoming the world’s most sustainable yacht business. By 2030 we aim to introduce an entirely self-sufficient yacht, including hybrid propulsion with solar power,” declares chief executive Ashley Highfield. Unique features such as its signature deck saloon, which creates a lighter interior so seascapes unfold through triple windows, have long made Oyster a favourite. Ashley Highfield, Oyster Yachts CEO (Image: Oyster Yachts) Like many of the parts, such as the stainless steel ones, manufacture of its range of 50ft to 90ft craft (from £1.5 million to £9 million) is carried out in the UK. Some 90,000 hours goes into building each 90ft flagship and its 50ft entry model, the 495, is the magnet for a new generation of Oyster owners. Supporting 500 skilled jobs, operations across Oyster’s three sites – Saxon Wharf and Hythe Marine Park in Southampton and Wroxham in Norfolk – are expanding with new facilities. A foundation for the next generation is also being laid with the company’s apprenticeship academy. Latest results testify to Oyster’s buoyancy with growth increasing 29 per cent year-on-year, a £56.4 million turnover for 2022/23 and an in-profit forecast for this year. It’s an achievement even more striking given the 51-year-old company’s recent history when in 2018 it was heading for the rocks. Rescue came in the shape of tech entrepreneur, customer and Nelson devotee Richard Hadida who stepped in to guarantee its future, committing a further £14.5 million investment in a five-year turnaround plan. In 2022 a record 22 yachts were launched and now the company is shipshape technologically and will soon release an app so owners have real time access to their yacht’s systems with easy connection to customer care and the wider Oyster community. Further development of its Mediterranean service centre in Palma is also underway. For many owners (could they be Oysties?) regatta allure is strong and the experience of being part of the biannual Oyster World Rally, a 16-month circumnavigation of the oceans covering 27,000 nautical miles and 27 destinations, is a pearl beyond price. 2026/27 is fully booked making 2028 the current option.

Key Yachting is delighted to announce the return of MDL Marinas as a sponsor of the 2024 J Cup Regatta. This marks the second consecutive year of MDL’s sponsorship, highlighting a longstanding partnership that spans many years and numerous MDL marinas across the country, including Key Yachting’s base at Hamble Point Marina. As the UK’s leading marina and water-based leisure provider and one of the largest marina groups in Europe, MDL Marinas boasts 18 prime locations in the UK and one in Spain. In a show of support, MDL Marinas will be providing the popular J Cup caps to every sailor taking part in the race, a treasured item among participants. Tim Mayer, MDL’s Sales and Marketing Director, commented, “We’re delighted to sponsor the regatta, offering sailors of all abilities an opportunity to get out on the water and enjoy the sport they’re so passionate about. We are also proud to support the team at Key Yachting, who are an integral part of our marina community.”

Kill cords

What is a kill cord? A kill cord is a coiled red lanyard fitted with a quick release mechanism. When used correctly, a kill cord will stop a boats engine if the driver becomes dislodged from the helm position. Proper use of the device can prevent serious incidents and even fatalities. Attaching the kill cord Kill cords contain a quick-release fitting at one end and a clip at the other. When in use, the quick-release fitting is attached to the console and the clip is attached to the driver. Your kill cord should always be clipped back onto itself. It should not be clipped back onto an item of clothing or attached to any other location. Typically, it will be fastened around the driver’s knee and clip back onto itself. A kill cord must be worn by the driver whenever the engine is running. Should you for any reason not wish to attach the kill cord around your leg, attach it securely to your personal buoyancy. In either case it should not foul the steering or gear controls. Kill cord design The cord is coiled in its design so that it can expand and allow for natural movement whilst helming a boat. Should the driver move away or be thrown from the helm position, the kill cord will detach from the console causing the engine to stop. Detaching the kill cord also allows the crew or passengers to stop the engine if the driver is incapacitated or unconscious at the helm. In most instances a boat will not start without a kill cord in place. Therefore, a second kill cord should always be kept onboard to re-start a boat if both the driver and their cord fall overboard. Kill cords intentionally prevent a driver from moving away from their normal operating position. Because of this, it can be tempting to use a kill cord that is longer than the item provided by the manufacturer of the engine. However, longer kill cords are not as taut as shorter ones, taking longer to react in emergency situations. If you need to leave the command position, or change driver, always turn the engine off. The engine should only be re-started when the kill cord has been secured to a new driver. Check the kill cord works Always test your kill cord at the start of each day or session. Do this by starting the engine and pulling the kill cord to make sure it cuts the engine. Monitor the kill cord for signs of wear Kill cords should be protected from the elements. Over time, extremes in temperature and UV light will harm the lanyard. Kill cords may become stretched or brittle if stored open to the elements. Monitor your kill cord for signs of wear, rust, and reduced elasticity. Make sure to replace it in good time before returning to the water. When replacing kill cords, purchase a good quality lanyard with a strengthening cord through the middle. Most chandlers will stock kill cords to suit common engines, but if in doubt visit the RYA shop. Summary of RYA advice and recommendations: Attach the kill cord around your leg, it should not foul the steering or gear controls. Do not extend the length of a kill cord provided by engine manufacturer. Always check your kill cord works at the start of each day or session. Purchase a good quality lanyard with a strengthening cord through the middle. Do not leave kill cords out in the elements. Always keep a spare kill cord on board Wireless kill cords As an alternative to the traditional red lanyard, wireless kill cords are also available. This type of kill cord will stop the engine when a personal device on the helm’s person, is out of range from a sensor. Always research and seek advice on the suitability of an alternative kill cord device for your engine before use. Posters Download and print a kill cord poster to put up in your club. Poster 1 and Poster 2 Kill cord stickers Each sheet of THiNK! WEAR YOUR KILL CORD stickers includes 3 stickers of different sizes and designs. Stickers are currently supplied by the RYA free of charge at our discretion. Small quantities of stickers will be sent to members, clubs and centres on request. Where possible, we will also support non-members and other businesses in the UK with stickers. The quantity requested should be limited to your immediate need. Bulk requests for stickers can be submitted but must be supported by information detailing how the stickers will be used and over what period of time. If you would like to request some stickers, please complete and submit this form.

Source: Kill cords